When Common Goals Unite

/Pakistan, being a country with a long, rich history, has no shortage of stories, but unfortunately they have not been written down nor printed for teaching children to read. The ASER 2015 report found that 84% of students in Class 3 could not read a story in Urdu, the national language, Sindhi or Pashto. Textbooks for teaching reading are important but ineffective without the support of additional reading material like storybooks in classrooms. Yet most Pakistani classrooms are not equipped with educational materials that promote reading.

USAID has two reading projects in Pakistan currently. First, the Pakistan Reading Project (PRP) which is a national reading program to improve teacher training and the availability of materials that supplement reading textbooks. The hope for the project is that teachers will be better trained to teach reading but also to improve access to materials through libraries in classrooms and even mobile libraries that will reach 300 communities. The project could reach as many as 23,800 teachers in public schools with improved skills in teaching reading in the national language of Urdu and also assessing their classrooms.

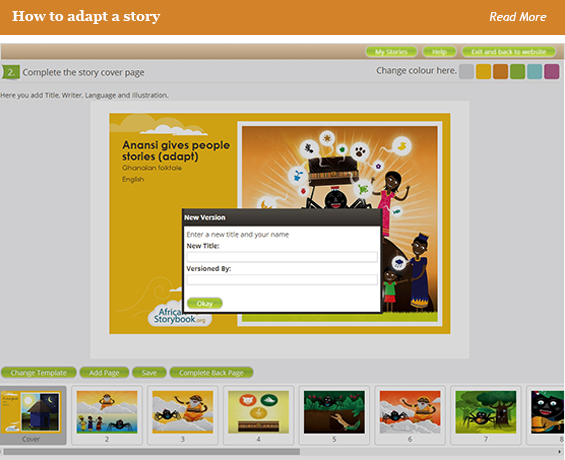

Norbert Rennert, a researcher at the Canada Institute of Linguistics and the creator of SynPhony technology, was able to share SynPhony with those training teachers in the Pakistan Reading Project. Because learning in Pakistan often involves rote memorization and copying text books, retention and comprehension is very low. Putting together new phonics methods and materials is difficult with lesser studied languages. SynPhony was created to do the analytics necessary to determine the order that letters and sounds should be taught to create effective teaching and reading materials.

Similarly the second USAID project in Pakistan—the Sindhi Reading Program—aims to address critical issues in early-grade reading and mathematics through continuous teachers’ professional development, improving assessment, distributing supplementary materials, and encouraging family participation. The Sindh province of Pakistan is the second largest region of the country and there are 18 million Sindhi people throughout the whole country. Sadly illiteracy is quite high in the mother tongue and about 4 million Sindhi children aged 5-12 are not even in school.

“Sindhi is a very old language and has a rich literary history,” observed Norbert Rennert recently. “I was impressed with the way the Sindhi speakers love their language and seem to be very determined to make sure it stays alive and vibrant.”

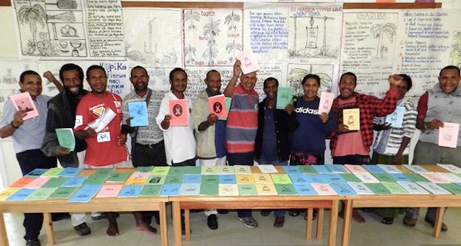

Rennert also went to Pakistan last year to facilitate a training for the Sindhi Reading Program. There he was able to meet a group of Sindhi speakers and share with them how SynPhony is being used to create curriculum for their schools.

The group in that Norbert spoke to in this training had gathered to develop literacy standards for Sindhi. And they responded with much enthusiasm and appreciation to know that, despite being a stranger to the Sindhi people, Norbert created SynPhony with people just like them in mind. The common goal of helping children to learn to read and write in their mother tongue brings together many people, crossing language and cultural boundaries.

To learn more about SynPhony visit http://call.canil.ca/.

In the news: