On a daily basis the Local language team and the English team discuss together how they can link the two languages. How can English make use of what has been learned in the Local Language first? Making use of what is known is called the ‘interdependence theory’ — what is learned in the first language will transfer to the new language once the learners have sufficient knowledge of the language.

Another way this transition is facilitated is by integrating some key English vocabulary in the local language books. All the page headers are in English. Each new concept introduced in week 1, practised in week 2, and applied in week 3 is also given its English name in week 3. So, once the children are familiar with the concept in their local language, they learn the English word for it. That will make it easier to make the transition: They know the concept in their local language, they know the label for it in English, and now they can use it in English as well. (This assumes, of course, that they have sufficient vocabulary to express themselves in English.)

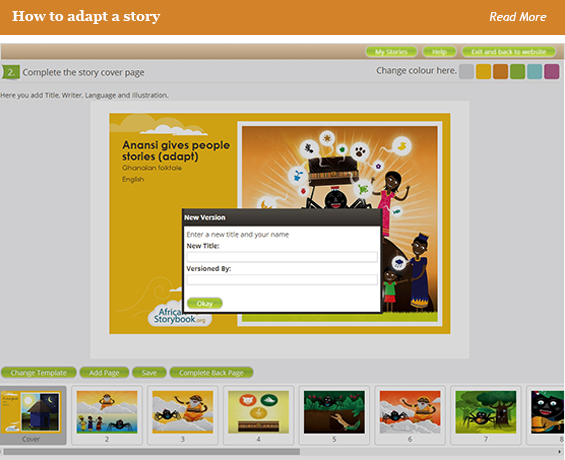

While everyone is writing, drawing and thinking, the typists keyboard all the outputs. They type away, typing both in languages they know and ones they do not know. While the typists seem to be the last people on the book development chain, their role is crucial. Their work gives the teams feedback about whether sufficient, too much, or too little content was written. The typists transcribe all the lessons directly into the book design program Bloom. It has been developed and set up in such a way that with a little training, they can design the books.

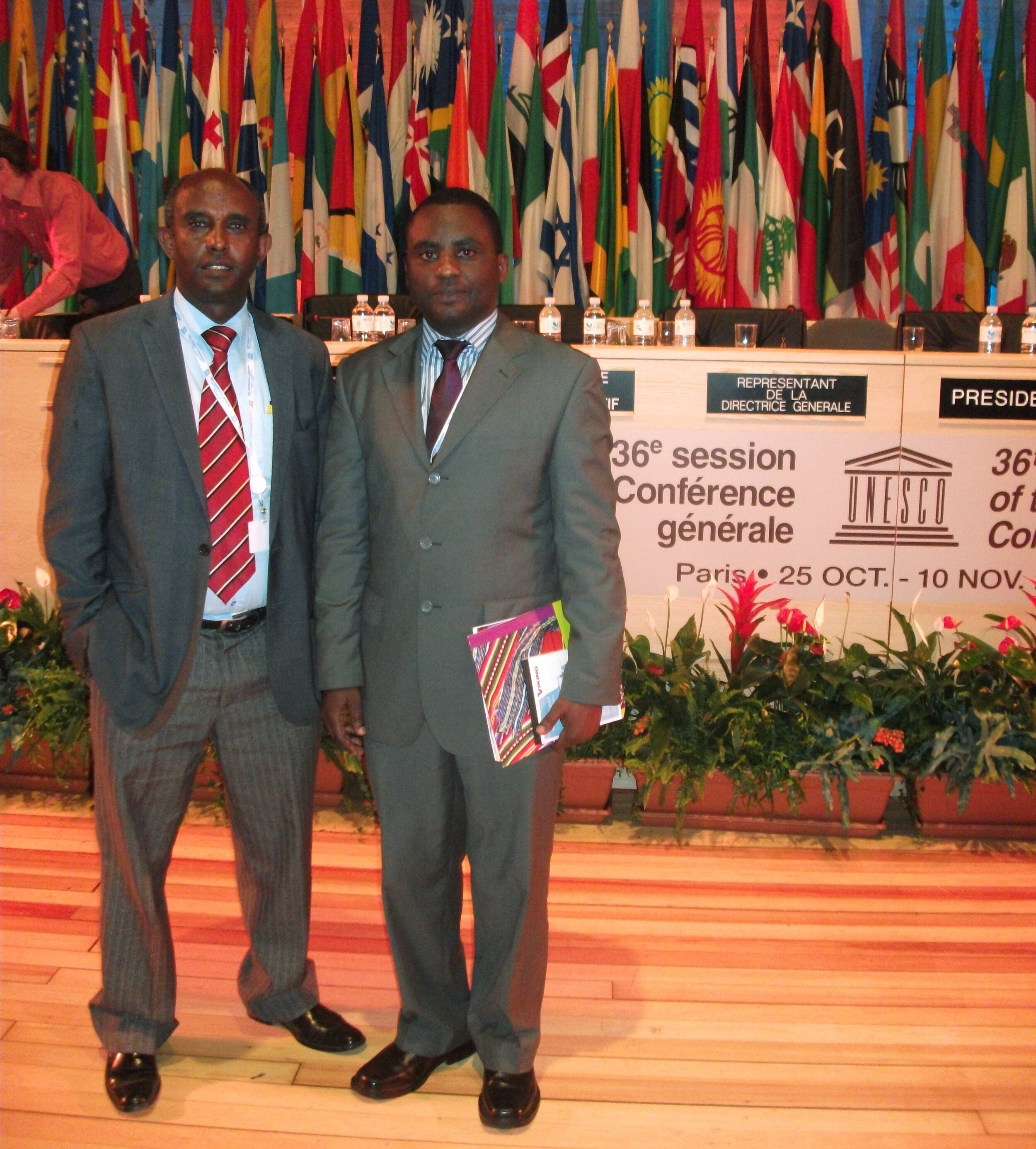

Materials development for grade 4 is a dynamic process with many different parts. Excitement is in the room as stories are prepared, lesson are written, and illustrations are drawn. Facilitating this process is exciting and challenging at the same time. Days like today are good days—days in which I think I have the best job ever!

You can read more about the USAID School Health and Reading Program here.