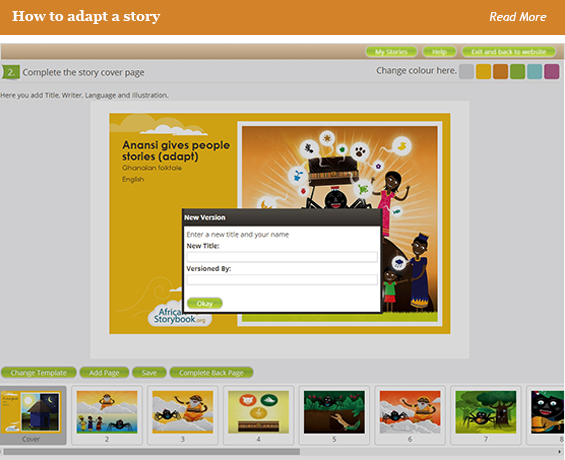

Another large difference is in the user interfaces. ICDL contains multiple ways to read, allows users to layer searches, and offers its interface in six different languages. The interface for the ASP is functional but still under construction. Users can search for books by language, type of story, and text level.

Currently, there are about 4,619 books in the ICDL, and about 2,412 in the ASP. While numbers are impressive for online collections, they are only a fraction of the 12,000 books available in a typical American school library. However, ASP’s collection is growing rapidly, with the number of texts increasing by about 70% in as little as four months. Because of the emphasis on quality, ICDL’s collection is growing more slowly, and activity on the site dropped precipitously after 2011. Still, both collections provide reading material for students that might otherwise have trouble getting reading material. Such students include Lumasaaba-speaking children in Uganda, who can now access 69 books on the ASP website. It also includes American students who speak Farsi with their parents, and who can now access 476 books on the ICDL website.